08 Aug Use of robotic surgery expands in Wichita area

In about five years, the Wichita area has gone from one surgical robot at Via Christi Hospital on Harry to eight robots at five regional hospitals: Wesley Medical Center, Newton Medical Center, Hutchinson Regional Medical Center and Kansas Medical Center, in addition to Via Christi.

Over the same time, use of the da Vinci Surgical System, manufactured by California-based Intuitive Surgical Inc., has grown from prostate removal and hysterectomies to heart surgeries performed at Kansas Medical Center in Andover.

Credit for the growth locally can be attributed to a combination of hospital marketing efforts, competition and what hospital executives and surgeons said are faster recovery times and other improved health benefits for patients from a high-tech system that requires a few small incisions versus one or more large ones and is generally less intrusive on the human body.

The expectation is that use of the da Vinci over traditional, “open” surgeries will continue to grow as more surgeons broaden their skills on the system.

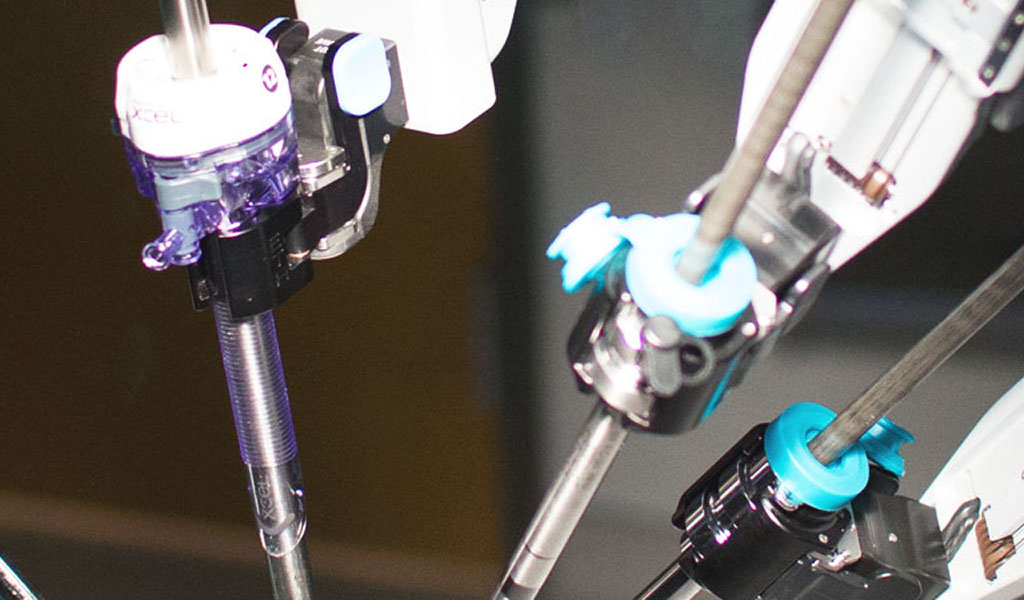

The so-called robot does not do the surgery itself. Rather it’s the surgeon who sits at a console several feet away from the patient who guides da Vinci’s spider-like arms, which hold tiny, sophisticated tools that do the work of the surgeon’s hands, as well as a three-dimensional camera that magnifies the surgical site for the surgeon at the console and on flat-panel screens in the operating room.

One of the system’s biggest selling points, executives and surgeons said, is its ability to act like a human wrist but with greater range of motion, such as turning 360 degrees, which a human wrist cannot.

The system is not cheap. It has a price tag of more than $1 million. And some of the instruments that attach to the robot’s arms have to be replaced after 10 surgeries, while others can last for as many as 20 surgical cases, said Brian Swallow, director of surgical services for Via Christi Hospital on Harry. “Tiny gears and other (components) start to wear down,” he said.

Just as crucial as the machine is the surgeon who can use it. “When you go to the robot, there’s no feel,” said Badr Idbeis, a cardiothoracic surgeon and CEO of Kansas Medical Center. “It’s all visual, visual-tactile. There is a lot of skill that has to be developed.”

Surgeons are trained on the robot by its maker, Intuit in California. Part of the training involves learning to use the system in a pig lab, Swallow said, and then on humans with assistance from surgeons who are experienced in using the system.

Idbeis, for instance, said his training involved learning from surgeons using da Vinci at the Cleveland Clinic and in Greenville, N.C. Since installing the da Vinci at Kansas Medical Center, Idbeis estimates they have done more than 30 surgeries with the robot, including heart surgeries he has performed. He said the system is also used at his hospital for urologic surgeries.

At the beginning of the year, Via Christi took delivery of its third da Vinci system. It also purchased a robotic training simulator to improve surgeons’ skills. The simulator also tracks their progress on the simulator over time. Swallow said it’s especially helpful for certain types of robot-assisted surgeries that have lower volumes than others.

In May, Wesley Medical Center also took delivery of its third da Vinci system. Wesley began using its first robot in 2010. Becky Klungreseter, Wesley’s associate chief nursing officer who oversees surgical services, said the system has proved itself in terms of reducing recovery time for surgical patients. She said some patients also report less pain after surgery with the da Vinci, in some cases not needing their post-surgical pain medications.

“It’s exciting,” Klungreseter said. “Patients recover faster; there’s less tissue damage.” On bowel resections, she said, there is less bleeding. And on single-site surgeries using da Vinci, there is less scarring, she added.

“If outcomes is what you are seeking, then this is the best on multiple levels,” she said. “But at the same time, it takes the skill of the surgeon. The robot does not run itself.”

Standard of care?

From one insurer’s perspective, use of the da Vinci is not to the point where it’s a standard of care. And hospitals that are using the robots aren’t reimbursed extra money for their use.

“It’s really up to the providers, what they want to use,” said Mary Beth Chambers, spokeswoman for Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas. “The robotic surgery technology is still relatively new. There aren’t a lot of studies yet showing … that it really improves outcomes and the efficiency of surgery, so the jury is still out a little bit on that.”

Chambers added that her company does not try to “practice medicine” and leaves it up to providers to determine the best way to do a surgery. Reimbursement, she said, is based “more on the procedure and not necessarily the technology that’s used, and that’s across the board with all medical services.”

Hospital officials acknowledge that they don’t get any extra reimbursement for using da Vinci over traditional surgery.

“You pretty much cut into your margins,” Kansas Medical Center’s Idbeis said. “The hope is that you make up for the lower margins by higher referrals. It doesn’t always work that way.”

But Idbeis and other hospital officials said they are convinced that in some instances it has become a standard of care and an expectation of patients.

“I think we live in a competitive market, and it’s a small area, and surgeons understand if they aren’t offering that kind of service they aren’t going to get (as many) patients,” said Brian Swallow, director of surgical services for Via Christi Hospital on Harry. “We’ve all made the public aware that (robot surgery) is available, and so I believe they are looking for surgeons who are going to use it.”

Swallow and other hospital officials and officials do think the system has proven itself to improve outcomes and accelerate recovery.

Idbeis said a clear example of that is the heart surgeries he’s performed. With the da Vinci, he doesn’t have to “crack the chest” of a patient getting a heart bypass, for instance.

“Cracking the breast bone is what delays the recovery,” he said, adding that recovery for patients who have had their chest cracked can take four to six weeks versus patients whose heart surgery was performed with the da Vinci.

“I tell my patients they can go back to work anytime they want to within one to two weeks of surgery,” he said.

Idbeis added that not all patients are candidates for heart surgery using the da Vinci. For instance, if a patient needs both a bypass and a mitral valve repair, then traditional, or “open” surgery is required.

Just as the number of robots has increased, so, too, will the procedures.

Idbeis said pulmonary, or lung, surgery using the da Vinci may be the next service offered at Kansas Medical Center.

And Via Christi is expecting to add heart surgeries to its list of robot-assisted surgeries, Swallow said.

Wesley is hoping to do the same with hearts, Klungreseter said.

Nowadays, patients want to quickly get back to their lives after surgery. The da Vinci robot helps them fulfill that desire, officials said.

“It’s probably some continuous quest for newer and better technology that allows doctors to do a better job,” said Claudio Ferraro, president of Via Christi Hospital on Harry. “And I think it’s increasingly become a standard of care.”